Bob Babbitt Bass Anthology

Good Stuff Up Front

Here’s a short playlist of some of my favorite songs that Babbitt is credited for:

At the bottom I’ve also included a more comprehensive playlist that includes a wider range of Babbitt’s discography.

Bob Babbitt Biography

Bob Babbitt was born Robert Kreinar, in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, on November 26, 1937. Growing up he studied music, playing the double bass at clubs as a teenager.

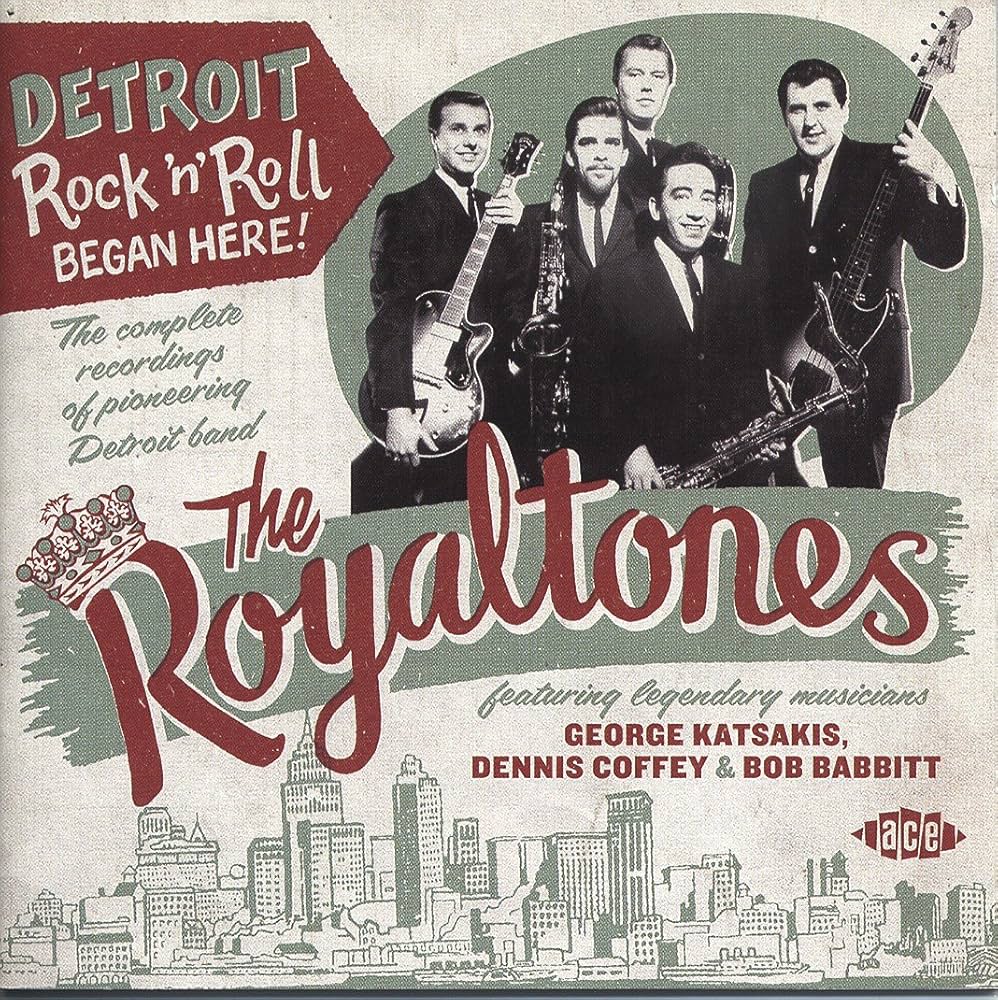

In the late 50’s, Babbitt moved to Detroit for work, where he later adopted the stage name Bob Babbitt and joined a group called the Royaltones in 1962. The Royaltones saw some success in the Billboard Hot 100 with songs like Flamingo Express, and even backed Del Shannon on many of his hits, such as Little Town Flirt and Handyman. Despite these successes, the group failed to break out on the national scene, and eventually disbanded sometime in 1964.

While the sun set on the Royaltones just a few years after Babbitt’s arrival, his star was still rising and he ended up joining Del Shannon’s band. By 1966, Babbitt was playing under Golden World Records in Stevie Wonder’s traveling band. It was through Golden World that he made his first connection with Motown Records. A year later, in 1967, Babbitt was asked to come in and sit in for the illustrious James Jamerson.

While there were many applicants in line to try and fill Jamerson’s metaphorical bass-playing shoes, Babbitt was the candidate to become the next member of Motown’s “Funk Brothers”. Babbitt himself ascribed his success in landing the role to his ability to sight-read music, helping him pick up new songs and styles quickly. Jamerson and Babbitt became friends, and while it is Jamerson who is synonymous with Motown bass sound, Babbitt was given room to express himself without being limited to imitating Jamerson. With regards to Jamerson, Babbitt once said, “He believed in freedom of expression and that you should make your bass sing like a voice.”

Babbitt would play along with Jamerson for Motown records until 1972, when Berry Gordy moved Motown Record’s headquarters to Los Angeles. Along with drummer Andrew Smith (another “Motown refugee”), Babbitt moved to New York and quickly found studio work. Following successes like Stephanie Mills’ debut album and Jim Croce’s I Got a Name, Babbitt caught the attention of Philadelphia International Records, and was soon commuting between the two cities to work with artists like the Spinners.

After bouncing between cities, albums, and musical styles, Babbitt’s time based in New York led to a certain amount of introspection. During his time at Motown, he’d never gotten permission to cut his own album, or an album with his rock-soul fusion infused band Scorpion, and often throughout his career was instructed to play in the style of other players. Biographer Allan Slutsky describes this period:

“On a personal level, New York had a profound effect on Babbitt. He went through a period of soul searching, questioning his long-time role as a sideman. “Throughout my career, I’ve been asked to be Jamerson or Chuck Rainey or Joe Osborn,” he points out. “This was the way producers communicated with me. I had never really thought about it. It used to bother me, but I came to realize the only way I could deal with it was to try to accommodate everyone while waiting for those occasional dates when a producer would just let me play. In Detroit, the guy who would do that was Norman Whitfield; on the East Coast, it was Arif Mardin and Thorn Bell Thorn had a system: He would always write a note-for-note chart for you. If there was no chord symbol over a bar, you had to play it as written; if there was a chord symbol, you could either play the part or do something else you felt like doing. Looking back, I think the tracks where the real me came out are Touch Me in the Morning, Then Came You, Mama Can’t Buy You Love, Midnight Train to Georgia, and Dennis Coffey’s Scorpio, which had a 90-second bass solo that’s all me.””

The ability to pick up songs and other styles that had once given Babbitt the momentum it needed to rise to fame, now seemed to be in some ways stifling his self-expression. As with many problems that come with the weight of being too successful, the pressure and identity crisis that came with the massive workload Babbitt saw in the late 70’s eventually resolved themselves. With the 80’s rolling in, Babbitt found less studio work and spent more time on side projects, or touring with artists like Brenda Lee, Herbie Mann, and Joan Baez.

Despite his hit factory days being behind him, Babbitt stayed active, quietly collaborating with a variety of artists in small projects over the decades. The last notably large project Babbitt played on would be Phil Collins’ somewhat self-indulgent celebration of Motown in the album Going Back circa 2010. A career that took off after Motown was bookended by his collaboration on a dozen songs celebrating that very same studio. A couple of years later, in June 2012, Babbitt was deservedly added to the Music City Walk of Fame in Nashville. Babbitt pass the next month, succumbing to brain cancer.

For those familiar with Standing in the Shadows of Motown, this might sound like a familiar narrative. It is hard to overstate the impact that Motown Records had on music in America. As one of the label’s “Funk Brothers”, Babbitt in turn was a part of that. His discography just from the year 1970 alone is incredible:

- Ball of Confusion

- Band of Gold

- Give Me Just a Little More Time

- Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I’m Yours)

- Stoned Love

- War

Despite being justifiably associated with the label, I do believe that Babbitt did make his bass “sing like a voice”. If you take a listen to his discography, particularly keeping in mind the wide range of genres he covered and musicians he collaborated with, his style becomes very recognizable.

If the drums are the skeleton of a song, then the bass is the heartbeat. (And the guitar is the rippling muscles. And the guiro is obviously the appendix.)

Babbitt’s style of bass has a punch to it. It doesn’t just keep the pace, it drives it. Slow ballads like Gladys Knight & The Pips’ If I Were Your Woman or Jim Croce’s I Got a Name get carried by the pulse that is Babbitt’s guitar. As an artist who may have taken off because of his ability to adapt, and spent part of his career feeling like a chameleon changing its colors to sound like other players and fit other styles, the voice of Babbitt’s bass guitar sings out pretty clearly once you know to listen for it.

Bob Babbitt’s work bridged music cities like Detroit, New York, and Philadelphia. It also bridged decades and musical genres. Although to some degree his music was bookended and overshadowed by his time with Motown Records, his own bass-playing style still comes through and has left it’s distinct mark on American music. I’m glad I dug into his discography, and I hope you enjoy listening to it. Here’s my take on a Bob Babbitt anthology.

Until next time,

-WellTree